HUMAN RIGHTS

|

| ||||||

|

When Do Closed Camps Become Prisons by Another Name?

The Yale Journal of International Law (2022) |

The Islamic State’s Pattern of Sexual Violence: Ideology and Institutions, Policies and Practices (with Elisabeth Jean Wood)

The Journal of Global Security Studies (2020) |

|

There is an inherent tension between the widespread practice of establishing camps to provide temporary housing and humanitarian assistance to migrants and the fundamental human right to freedom of movement. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), some degree of limitation on rights—including movement—is “the defining characteristic” of camps. International law permits states to impose some restrictions on the movement of migrants, including temporary confinement in “closed camps,” for lawful purposes including identity verification and security screening in situations of war, emergency, or other grave and exceptional circumstances, but subject to important limitations: restrictions must be proportional, non-discriminatory, and time-limited. Closed camps, from which residents are not free to leave because they are suspected of presenting threats including crime, extremism, or disease, are a relatively recent development in the modern migration management regime and have become more common over time in a trend that is likely driven by the increased frequency of subnational conflicts resulting in high levels of internal displacement and the growing securitization of systems for managing large transnational flows of “mixed migrants.” U.N. agencies have provided some general guidelines on the human rights and humanitarian conditions that must be satisfied in order for closed camps to comply with international law including access to education, healthcare, documentation, and courts, as well as communication and contact with family. However, in practice, the states and non-state actors who manage closed camps can and have violated these conditions with impunity in the absence of accountability mechanisms to enforce their compliance. This article uses a case study of Al-Hol, a closed camp in northeast Syria where more than 56,000 people—mostly children and women—from at least sixty different countries have been confined since 2019 on suspicion of having family or other ties to the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIL) to illustrate how closed camps can become open-air prisons by another name and therefore require close monitoring and further study.

|

The Islamic State, which controlled significant territory in Iraq and Syria between 2014 and 2017, engaged in a wide repertoire of violence against civilians living in these areas. Despite extensive media coverage and scholarly attention, the determinants of this pattern of violence remain poorly understood. We argue that, contrary to a widespread assumption that the Islamic State wielded violence indiscriminately, it systematically targeted different social groups with distinct forms of violence, including sexual violence. Our theory focuses on ideology, suggesting it is a necessary element of explanations of patterns of violence on the part of many armed actors. Ideologies, to varying extent, prescribe organizational policies that order or authorize particular forms of violence against specific social groups and institutions that regulate the conditions under which they occur. We find support for our theory in the case of sexual violence by the Islamic State by triangulating between several types of qualitative data: official documents; social media data generated by individuals in or near Islamic State-controlled areas; interviews with Syrians and Iraqis who have knowledge of the organization’s policies including victims of violence and former Islamic State combatants; and secondary sources including local Arabic-language newspapers. Consistent with our theory, we find that the organization adopted ideologically motivated policies that authorized certain forms of sexual violence, including sexual slavery and child marriage. Forms of violence that violated organizational policies but were nonetheless tolerated by many commanders also occurred and we find evidence of two such practices: gang rape of Yazidi women and forced marriage of Sunni Muslim women.

|

| ||||

|

"I Am Nothing Without a Weapon": Understanding Child Recruitment and Use by Armed Groups in Syria and Iraq

|

|

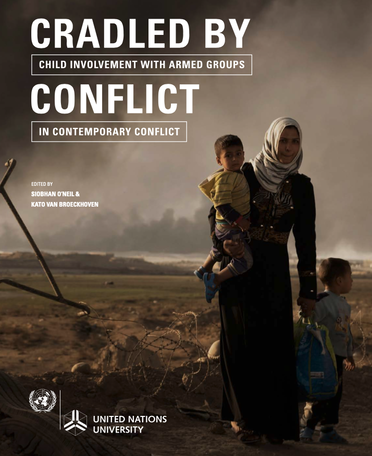

Chapter 4 in Cradled by Conflict: Child Involvement with Armed Groups in Contemporary Conflict (O'Neil, Siobhan, and Kato van Broeckhoven, eds.), United Nations University, 2018.

Short article summary in The Washington Post |

|

The Syrian civil war, which began as a peaceful uprising in 2011, has since devolved into the deadliest conflict of the 21st century. According to United Nations estimates, the death toll had reached 400,000 by April 2016, and 7.6 million Syrians (40 per cent of the country’s population) have been displaced, either internally or as refugees to other countries. The conflict has spilled over into neighboring Iraq, where Islamic State (IS) seized a third of the country’s territory in June 2014. These two related conflicts have had particularly devastating consequences for Syrian and Iraqi children, many of whom have been orphaned or otherwise separated from their parents. In addition to facing the physical dangers of injury or death, children experience emotional and developmental challenges associated with exposure to extreme violence, the loss of family members or friends, and multi-year interruptions of schooling. Children are targets for several types of exploitation that are particularly prevalent in conflict settings: child labour, sexual abuse, early and coerced marriage, human trafficking, and, of particular concern for this study, recruitment and use by Government armed forces, pro-Government militias, and non-state armed groups (NSAGs). Existing explanations for the motivations of children who join such groups often focus on single variables, such as ideology or economic necessity, without examining interactions and correlations between different variables. Past work also tends to focus exclusively on the recruiting practices of a single group, without examining the trajectories of children who switch sides between two or more groups over time, even though such “side-switching” is commonplace in Syria and other multiparty civil wars. This chapter, based on months of multi-method fieldwork in four countries adjacent to Syria – Iraq, Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey – attempts to illustrate patterns of child recruitment and exploitation by NSAGs with new and rare data from key informants, including child recruits themselves. The chapter concludes with findings that are relevant for international and local actors working to prevent the recruitment and use of children by armed groups, as well as those seeking to facilitate the disengagement and demobilization of children who have already been recruited.

|

|